The algorithm I use to color graphs works pretty well … BUT:

- Sometimes (very rarely) it gets into an infinite loop where also random Kempe color switches (around the entire graph) do NOT work. The good is, if I reprocess the same graph from the beginning (since in a part of the code I choose edges randomly), the algorithm

usuallyworks fine

So, what now?

I want to try other strategies while removing edges from the original graph, to avoid the above condition. I want to eliminate the need of random swithes.

The sequence I used so far is:

- Select an F2 and if an F2 does not exist, select an F3 an so on: F4 and then F5. Once selected the face, I remove a random edge from it, only paying attention not to chose the edge if the resulting graph is 1-connected

I want to try:

- Change the order of selecting the faces

- Combinations

- 2, 3, 4, 5 –> This is the default in the current version of the program (22/Nov/2016)

- 3, 2, 4, 5

- 4, 2, 3, 5

- …

- I want to try all possible combinations to see if … may be … if I’m really lucky, one does not require random swithes

- Combinations

- Once selected the face, I want to try other strategies to select the edge to remove

- random edge –> This is the default in the current version of the program (22/Nov/2016)

- Among all the edges of the face, select the one that is shared with the face that has less edges respect to the other F

- … that has more edges …

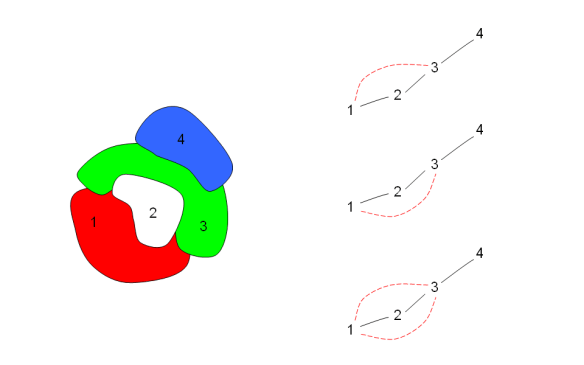

A planar cubic graphs to visualize what I wrote in this post: