I still think a solution may be found in Kempe chain color swapping … for maps without F2, F3 and F4 faces (or even without this restriction).

Or at least I want to try.

How you can solve the impasses (To be finished):

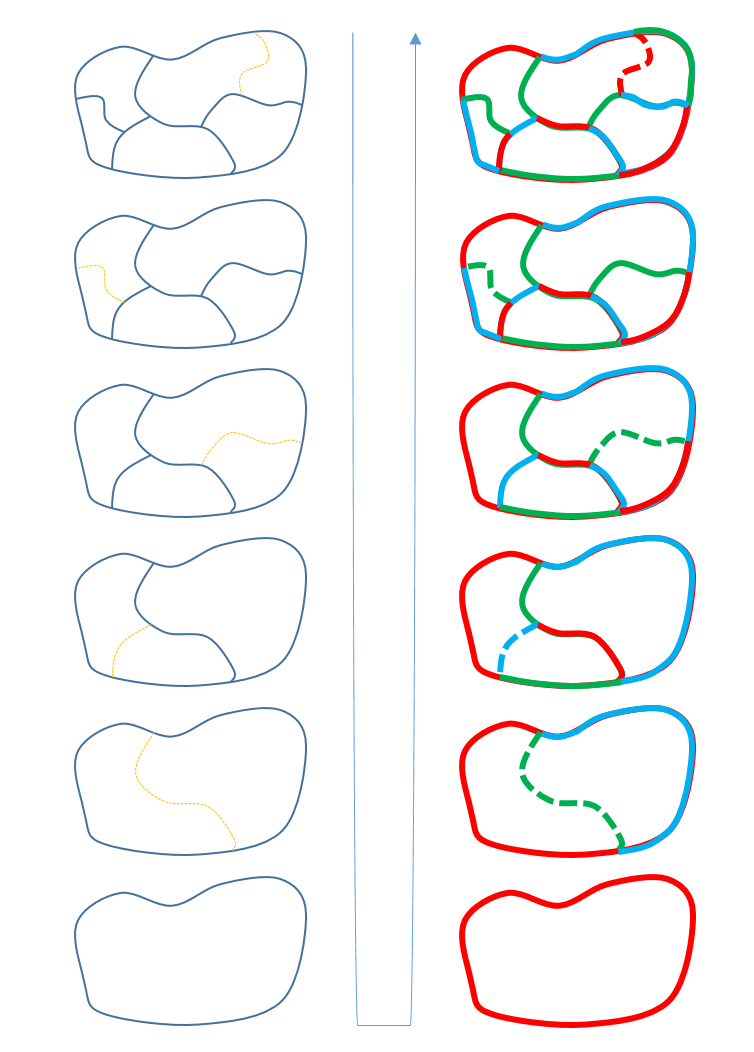

To explain the possible cases, without lack of generality, I can assume to start with these colors: e1=red, e2=green, e3=blue, e4=red. e4 may also be colored in green, the reasoning will not change much.

- If e3 and e4 are not colored … there is no impasse → OK

- If e3 is the same color ex should be (blu in the example) and e4 is non colored

- If one of the two possible chains starting from e3: (b, r)-chain or (b, g)-chain does not end at e1 or e2

- Use it to swap the color of e3 and solve the impasse → OK

- If both end at e1 or e2

- Try to deroute one of the two chains, using another kempe chain color swapping along the way, to fall into one the the solvable cases (2.A)

- If the derouted original chain does not longer end at e1 or e2, then apply the original kempe chain color swapping and solve the impasse → OK

- If deroute does not work

- … TBV: It seems that swapping colors around solve all type of impasses

- If e3 is the same color ex should be, and e4 is also colored

- In this case the chain (…-e3–e4-…) = (b, r)-chain would simply swap the colors of e3 and e4 and therefore will not solve the impasse. It is better to use the other (b, g)-chain, starting from e3

- If this chain does not end at e2 (e1 is not a possible end because the chain is blue and green), use it to swap the color of e3 and solve the impasse → OK

- If it ends at e2

- Try to deroute the chain, using another kempe chain color swapping along the way, to fall into one the the solvable cases

- If deroute does not work

- … TBV: It seems that swapping colors around solve all type of impasses

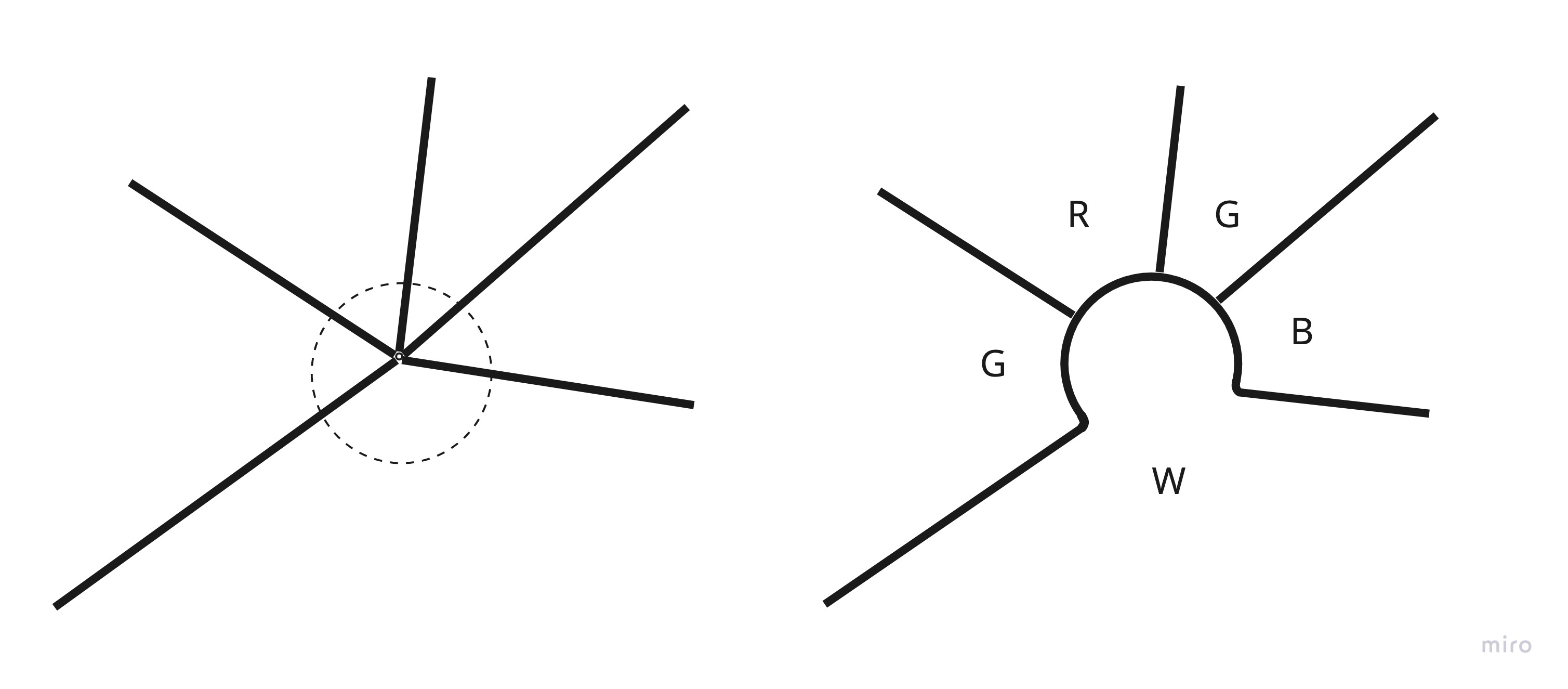

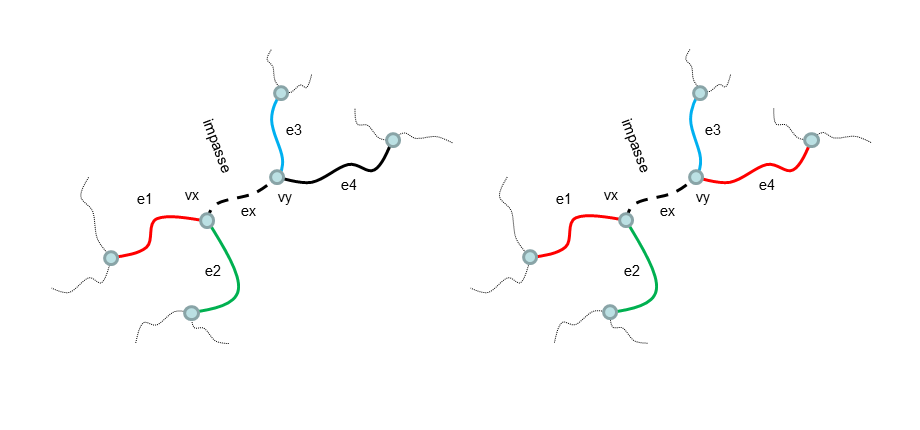

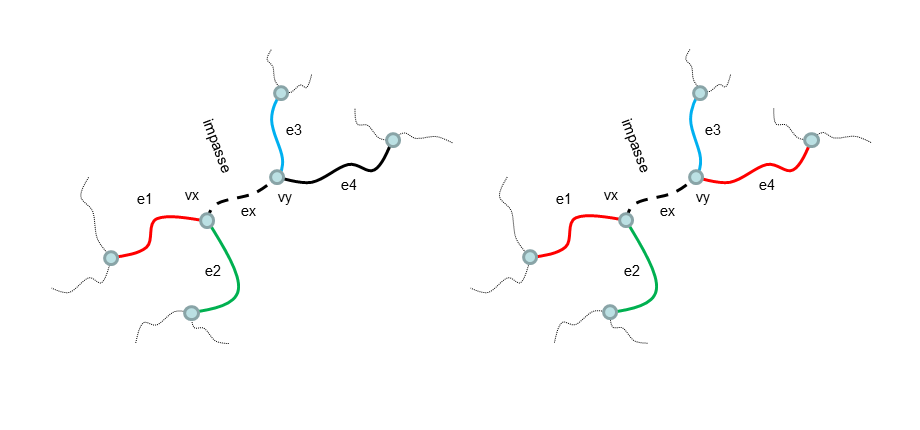

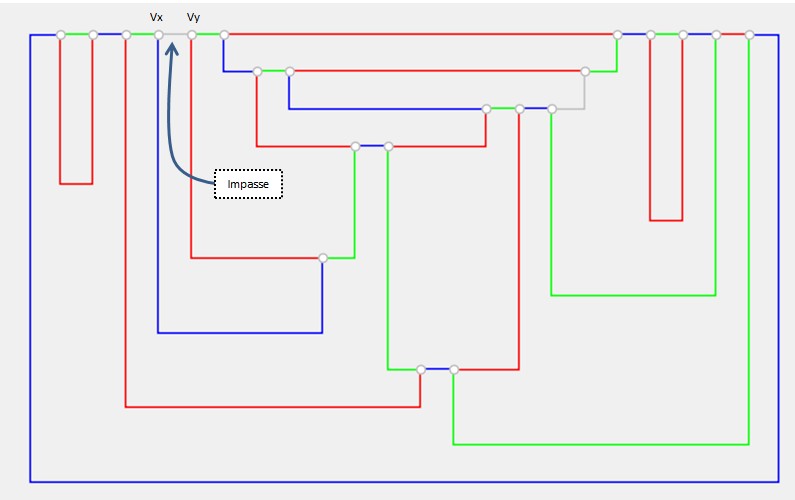

A deroute of a chain appears as in the next picture. Consider that deroutes may not work because Chain-B color swapping may change one or more of the three edges e1, e2, e4, and after appying the Chain-B swap, the chain starting with a3, may still end to one to e1, e2, e4. See this post for a real example: here.

About swaps of a partially colored map, I’ve asked a question on mathoverflow … here.

Maybe I was wrong when, in the motivation of the question (mathoverflow), I said that “I found many examples in which Kempe chain color swapping does not work for maps with faces of type F2, F3, F4, but I did not find an example of maps with only F5 or higher“. It seems to be possible also for maps with F2, F3, F4.

I’ll continue to search for counterexample but, for what I’ve seen so far (I tryed about 50 maps) it has been always possible to solve impasses, only proceeding by swapping colors.

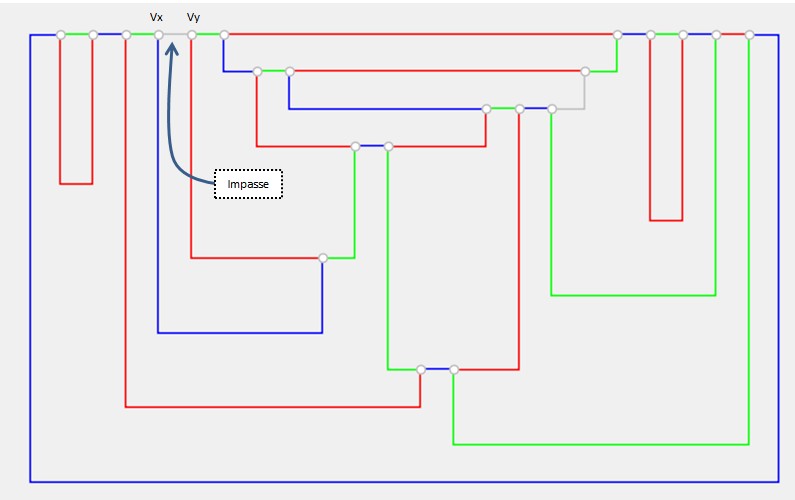

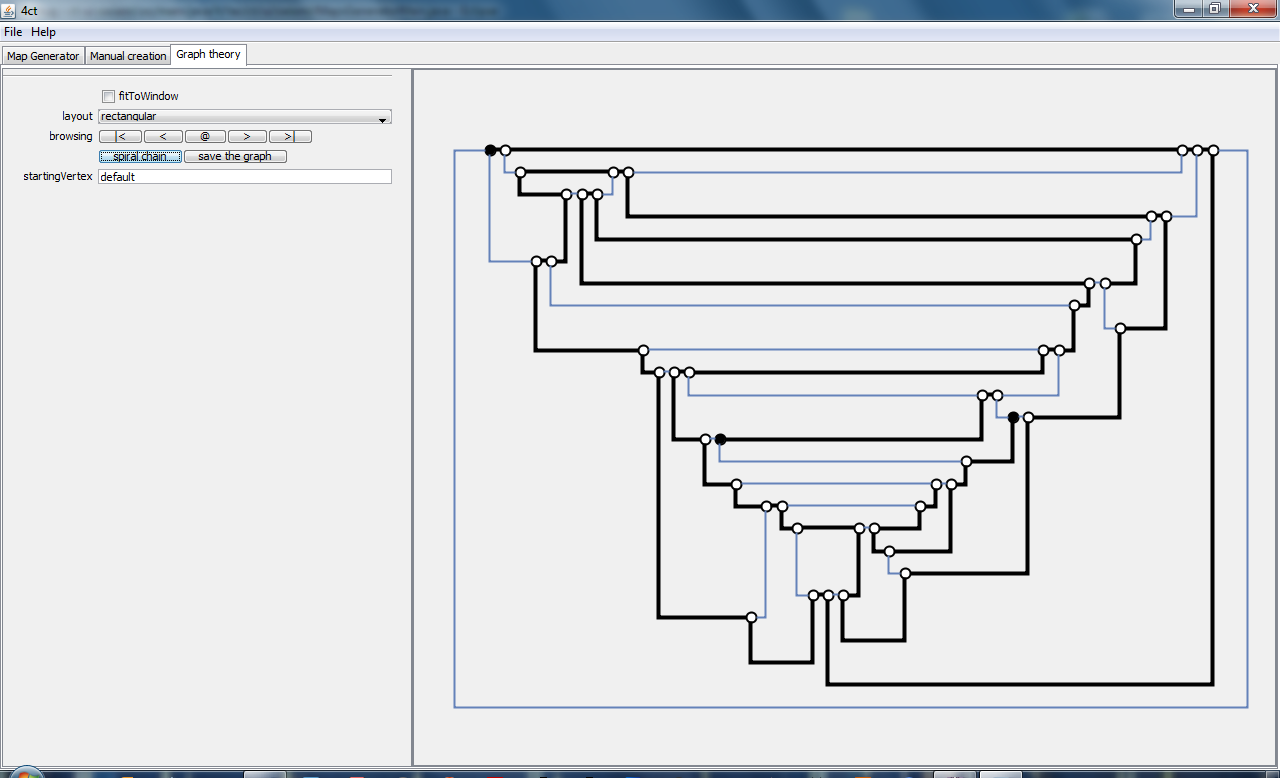

This is one of the map that I thought to be a counterexample, but it is not. Its signature is:

- 1b+, 9b+, 9e+, 3b+, 5b+, 7b+, 12b+, 10b-, 11b-, 5e-, 7e-, 4b-, 3e-, 2b-, 10e-, 4e-, 6b-, 11e-, 12e+, 8b+, 8e+, 6e+, 2e+, 1e+

Something else to check:

- Since once completely colored, all chains are actually loops, when it comes to the last two impasses, if you solve one impasse also the other one gets solved!