UPDATE (18/Apr/2011)

The nunber of proper colorings (not considering permutations of colors) can be count using the “Chromatic polynomial” and dividing the result by 4! (factorial that counts the permutations). But, the chromatic polynomial is only known for few types of graphs (Triangle K3, Complete graph Kn, Petersen graph, …). I haven’t found papers on this problem. Highly propably, since the difficulty to find the Chromatic polynomial of complex graphs, there cannot be a direct formula to calculate how many different colorings exist.

I’ve posted this question here on mathoverflow.

END UPDATE

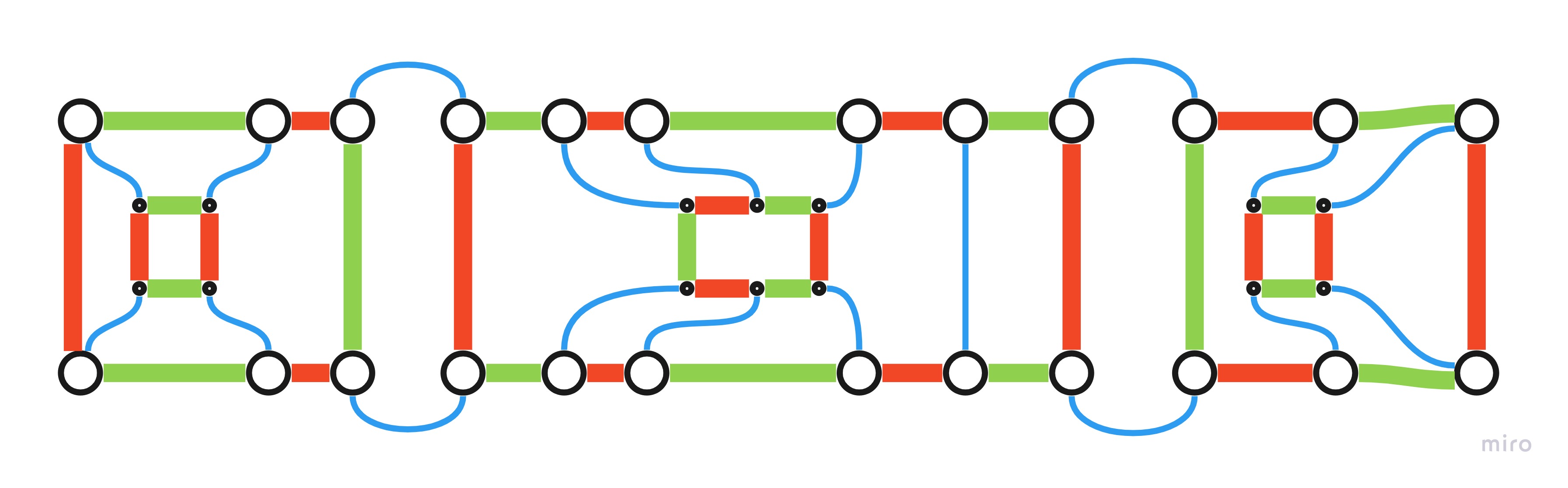

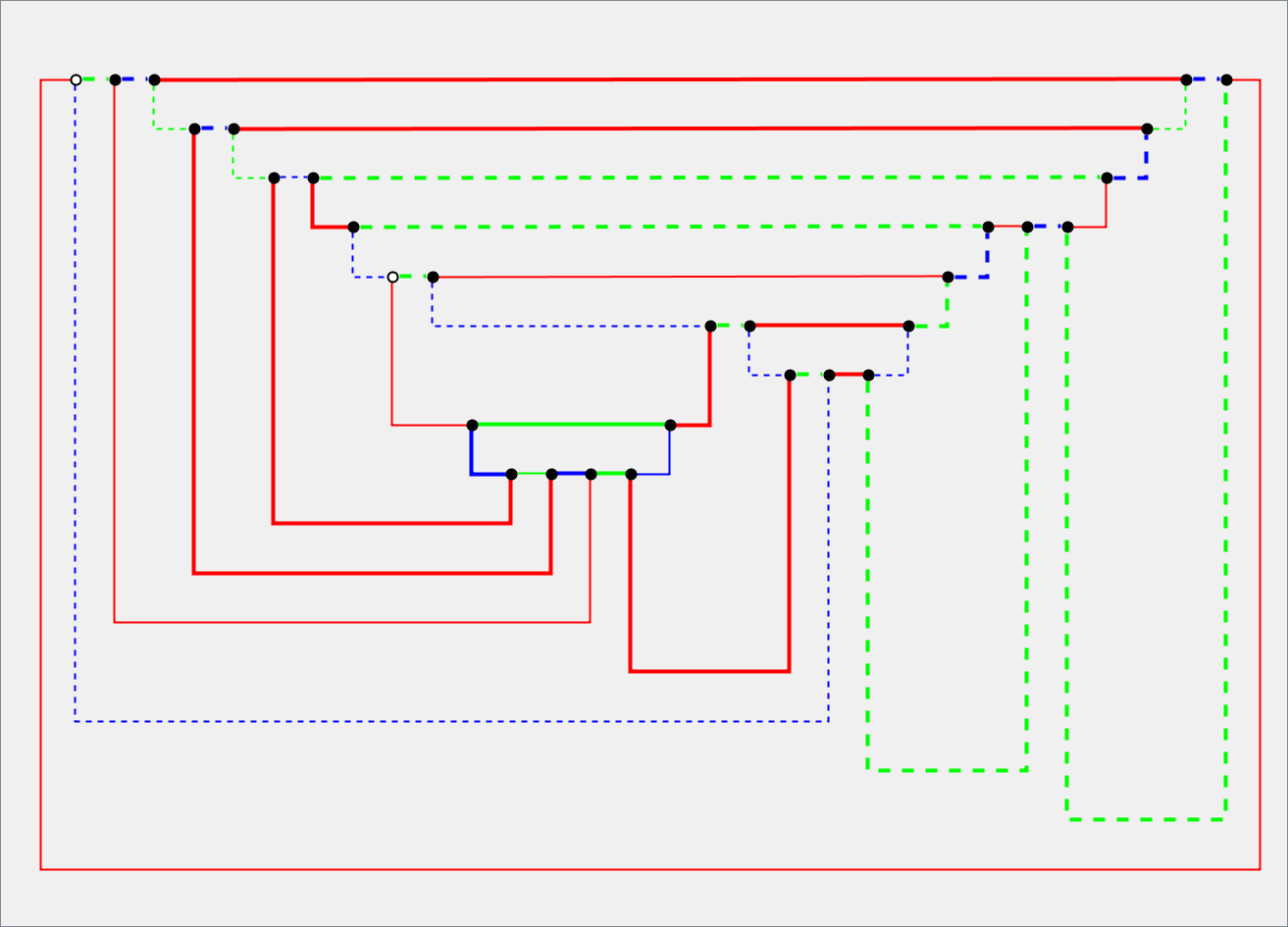

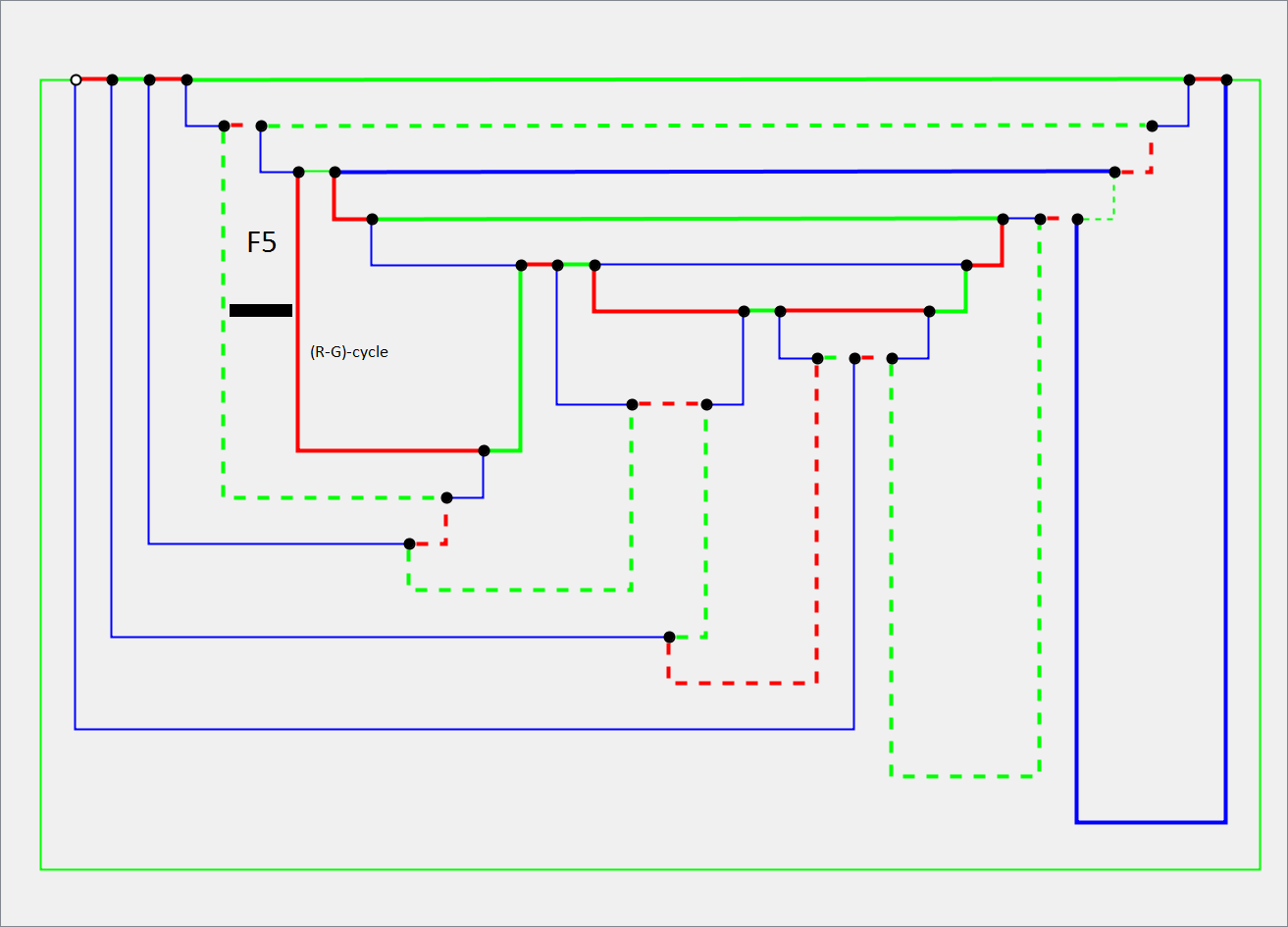

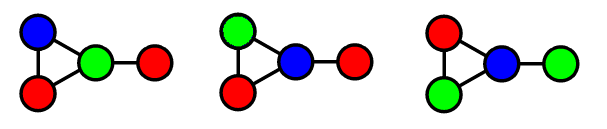

Take a look at these three graphs:

Are these really different colorings?

Before to dismiss this, do the following on the first graph:

- Change Blue to Yellow (Blue was just an arbitrary color among infinite others)

- Change Green to Blue

- Change Yellow to Green

Now you have the second graph. Continue with this:

- Change Green to Yellow

- Change Red to Green

- Change Yellow to Red

Now you have the third graph. Since the arbitrary nature of the choice of colors, the first graph could have been colored as the third one since the beginning.

The same result, can be obtained by changing all three colors of the first graph to three other colors. If applying the same method to the third graph, you can get the same configuration for the two graphs, it means that they can be considered, for some areas of investigation, as the same configuration.

There are more complex cases in which swapping colors won’t help to get from one coloring to the other.

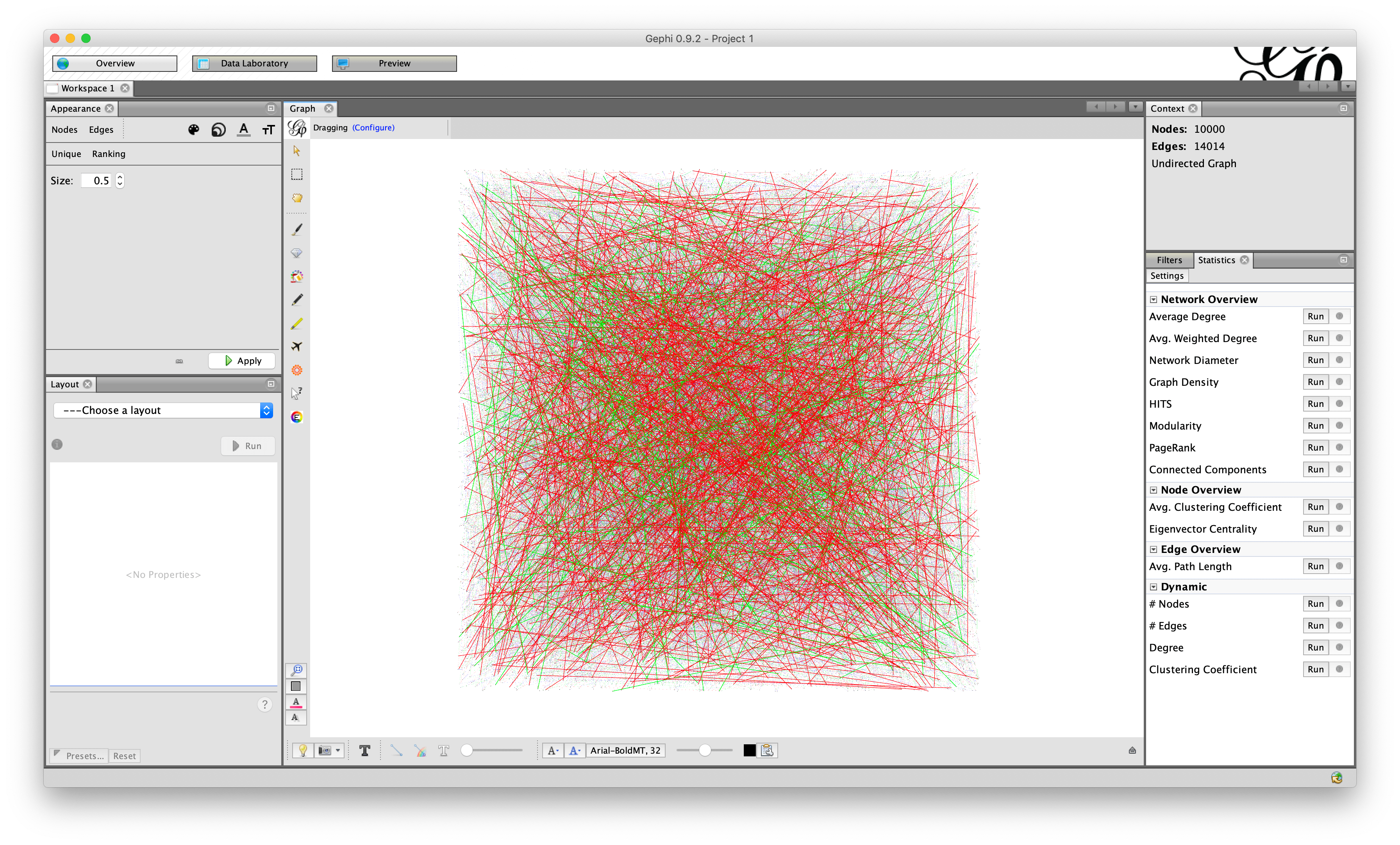

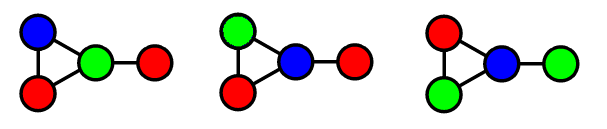

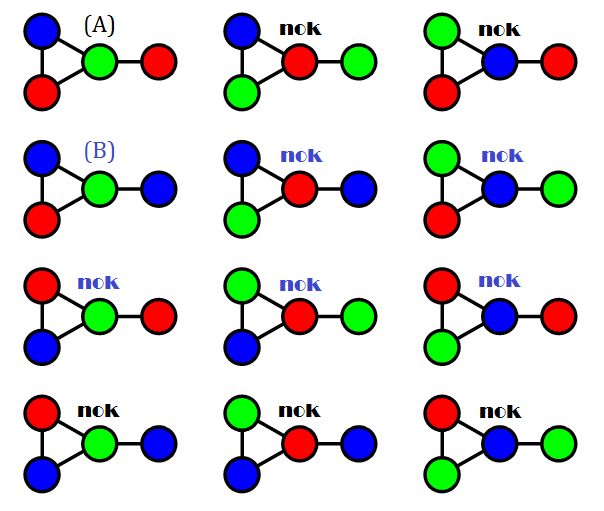

In the following picture taken from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Graph_coloring, the graphs named (A) and (B) are the only ones that cannot be converted into one another by swapping colors.

In particular I’m interested in regular maps, excluding all maps that can be colored with 2 or 3 colors. For what I need to analyze, maps have to be regarded as differently colored, if the same coloring cannot be obtained by subsequent exchanges of colors.

In other words, for example, once a map has been properly colored, I don’t want to count all other configurations that derive from subsequent exchanges of colors.

Since the arbitrary nature of choosing colors, these derived configurations are equivalent (for what I’m analyzing) to the first one, since they could have been obtained just choosing different colors in the first place. Instead, there are colorings that differ in such a way that exchanging colors won’t help to transform one configuration into the other.

My question is: how many “different” colorings (in the meaning I explained) exist for a given map?

I’ve only found an article on http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Graph_coloring that count all possible colorings including swaps.

Is there a paper that can help me on this?