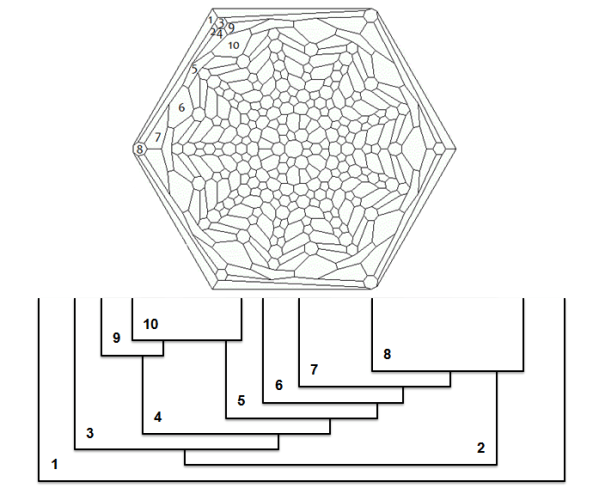

Haken and Appel map:

Taken from:

https://www.mathpuzzle.com/4Dec2001.htm (Ed Pegg Jr.)

Referenced by:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/49058045@N00/ (Ibrahim Cahit)

I just started to convert this map into a rectangular map.

To do it manually the full algorithm is explained in the page dedicated to the theorem T2.

Shortly:

- Consider the map as a jigsaw puzzle

- Number the faces of the original map starting from an external face

- Do not make holes while numbering the faces. Last piece will be the ocean (surrounding the entire hexagon)

- Get a piece from the original map (follow the numbering)

- Deform it into a rectangle

- Insert the piece into the rectangular map, respecting the topological properties of the original piece of the original partial map (do not consider the faces not already chosen). For example when you have to work the face number 6, imagine to walk on the border (clockwise) of the original face (the current piece of the puzzle) and write down the sequence of encounters you make. For face number 6 the encounters are: 2 and 5 (face number 6 doesn’t have to be considered because not yet chosen)

For the Haken and Appel map, the encounters are:

- face 1: no encounters (ocean is the last face to be considered)

- face 2: 1

- face 3: 2, 1

- face 4: 2, 3

- face 5: 2, 4

- face 6: 2, 5 (attention not to consider this sequence as a basic rule)

- face 7: 2. 6

- face 8: 1, 2, 7 (at this point face number 2 will be completely isolated)

- face 9: 4, 3

- face 10: 5, 4, 9 (at this point face number 4 will be completely isolated)

- …

Note:

- To do it manually after a bit of practice, it takes 10-20 minutes to convert the entire map

I did the same thing but differently. I took a planar map with vertices degree 3 or 4 and continuously deformed the map to place the vertices over (x,y) lattice points on the plane. Then I continuously deformed the connecting edges between vertices as integer steps. The result is an array of spreadsheet cells where regions consist of sets of edgewise connected cells, Neat and simple.

I assumed that the map so described could be successfully 4-colored (adjacent cells within the same region having the same color). I then took a 24 cell polytope in 4 dimensions and colored its 24 facets with 4 colors. Finally, I found a surjective mapping from the 4-colored two dimensional map M2 to the surface of the 24 cell polytope C24 such that: (i) adjacent cells in M2 correspond to adjacent facets in C24, and (ii) the color of any cell in M2 mapped to any facet in C24 has the same color as that facet (!) In other words M2 can be “wrapped” around C24 with the colors of the wrapping paper mapping the color of the underlying facets. In short, a successfully 4-colored M2 map is no more complicated that a 4-colored 24 cell polytope. Fun, eh?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Do you have some pictures that show your method? Or a paper?

LikeLike

I’d be happy to send you a copy of my paper. It will take a week or so to update. The method is quite straightforward and robust and has been confirmed by academics. If you can get an email address to me that would help. If I haven’t heard from you in a week I’ll find a download weblink for you. Cheers.

LikeLike

Thanks. Here is the email mario.stefanutti@gmail.com

LikeLike